The ruins of Ephesus – one of the largest archaeological sites in the world – are one of the best preserved of the many treasures of the Turkish coast and offer a glimpse of daily life in the classical world.

Once a key port on the eastern Mediterranean, despite repeated dredging, the harbour silted up, and what now remains of Ephesus lies a few kilometres inland. In its heyday, the city's markets were among the best in the classical world, and Ephesus achieved an importance that can only be imagined as you walk among the ruins.

Once a key port on the eastern Mediterranean, despite repeated dredging, the harbour silted up, and what now remains of Ephesus lies a few kilometres inland. In its heyday, the city's markets were among the best in the classical world, and Ephesus achieved an importance that can only be imagined as you walk among the ruins.

The city was one of twelve that comprised the Ionian League, an alliance of towns along the Anatolian coast of what is now Turkey. After the Roman conquest, the city became one of the largest and most important of the Empire, second only to Rome itself, and famed not only as a centre of commerce but also as a cultural, political and religious centre.

The city was one of twelve that comprised the Ionian League, an alliance of towns along the Anatolian coast of what is now Turkey. After the Roman conquest, the city became one of the largest and most important of the Empire, second only to Rome itself, and famed not only as a centre of commerce but also as a cultural, political and religious centre.

Hometown of the philosopher Heraclitus, and possibly the final home of the Virgin Mary, Ephesus was visited by Cicero, Julius Caesar, Cleopatra and Mark Antony, as well as by the emperors Trajan and Hadrian. Saint Paul may have written his first letter to the Corinthians when in prison here, and Saint John's tomb is in the ruined basilica, next to the Byzantine citadel overlooking the nearby town of Selcuk.

Hometown of the philosopher Heraclitus, and possibly the final home of the Virgin Mary, Ephesus was visited by Cicero, Julius Caesar, Cleopatra and Mark Antony, as well as by the emperors Trajan and Hadrian. Saint Paul may have written his first letter to the Corinthians when in prison here, and Saint John's tomb is in the ruined basilica, next to the Byzantine citadel overlooking the nearby town of Selcuk.

Ephesus was the first city in the world to have street lighting, and also boasts the earliest known advertising. The largest of the two theatres could hold an audience of 24,000 spectators, which gives an idea of the scale of the city at its peak. In 262 AD, Ephesus was destroyed by the Goths and, although it was not abandoned until several centuries later, the city's glory was eclipsed forever. Excavation of the remains was begun in the nineteenth century, and it is estimated that a scant twenty percent has yet come to light, although already what has been uncovered offers a fine open-air museum on a scale that will impress even those usually unmoved by ancient ruins.

Ephesus was the first city in the world to have street lighting, and also boasts the earliest known advertising. The largest of the two theatres could hold an audience of 24,000 spectators, which gives an idea of the scale of the city at its peak. In 262 AD, Ephesus was destroyed by the Goths and, although it was not abandoned until several centuries later, the city's glory was eclipsed forever. Excavation of the remains was begun in the nineteenth century, and it is estimated that a scant twenty percent has yet come to light, although already what has been uncovered offers a fine open-air museum on a scale that will impress even those usually unmoved by ancient ruins.

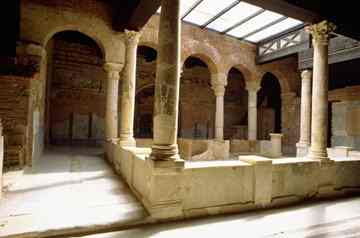

As you enter the main area, the streets on either side create a fabulous puzzle-like network from which you can reconstruct a picture of daily life in a thriving classical city. Next to the Magnesia Gate, built by Emperor Vespasian, are the eastern gymnasium – an education centre where the teaching of social studies, music, astronomy and sports went hand-in-hand – and the Varius baths, with some of the walls and vaulted ceilings still standing and its complex system of pipes. Then there's the odeon and the upper agora, where the senators debated, the temples of Domitian and Hadrian and what remains of the Prytaneion, the old town hall, between whose pillars the sacred flame of Hestia was kept burning.

As you enter the main area, the streets on either side create a fabulous puzzle-like network from which you can reconstruct a picture of daily life in a thriving classical city. Next to the Magnesia Gate, built by Emperor Vespasian, are the eastern gymnasium – an education centre where the teaching of social studies, music, astronomy and sports went hand-in-hand – and the Varius baths, with some of the walls and vaulted ceilings still standing and its complex system of pipes. Then there's the odeon and the upper agora, where the senators debated, the temples of Domitian and Hadrian and what remains of the Prytaneion, the old town hall, between whose pillars the sacred flame of Hestia was kept burning.

The most select residential houses were built around individual courtyards on the steep hillside, and close by, at the end of Curettes Road, is probably the city's most spectacular monument: the majestic two-storey facade of the Celsus Library. Back in the early second century this building housed no fewer than 12,000 scrolls, making it one of the largest repositories of knowledge in the ancient world. Alongside the library is the huge lower agora, the commercial area where shops traded in anything and everything that came in to the busy port.

The most select residential houses were built around individual courtyards on the steep hillside, and close by, at the end of Curettes Road, is probably the city's most spectacular monument: the majestic two-storey facade of the Celsus Library. Back in the early second century this building housed no fewer than 12,000 scrolls, making it one of the largest repositories of knowledge in the ancient world. Alongside the library is the huge lower agora, the commercial area where shops traded in anything and everything that came in to the busy port.

Farther on, beyond the great theatre and the Church of the Virgin Mary, past colonnades, mosaics, the ruins of fountains and other marvels, stands an inconspicuous column, almost the only remaining sign of the Temple of Artemis. The temple, dedicated to the many-breasted Lady of Ephesus, was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, but even Artemis – equivalent of Diana, the virginal huntress – failed to save Ephesus from destruction. Earthquakes and invasions combined to lay waste what was once the most powerful city in Asia Minor, although a walk through the ruins provides a hint of its former splendour.

Farther on, beyond the great theatre and the Church of the Virgin Mary, past colonnades, mosaics, the ruins of fountains and other marvels, stands an inconspicuous column, almost the only remaining sign of the Temple of Artemis. The temple, dedicated to the many-breasted Lady of Ephesus, was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, but even Artemis – equivalent of Diana, the virginal huntress – failed to save Ephesus from destruction. Earthquakes and invasions combined to lay waste what was once the most powerful city in Asia Minor, although a walk through the ruins provides a hint of its former splendour.

Source: Hello Magazine [December 01, 2010]