The changes in Arabia that set in with the Bronze Age were incremental and far-reaching and the objects from Saudi Arabia displayed at the Louvre repeatedly demonstrated the point. These changes extended far beyond the implications of smelting metal, however useful a technical ability.

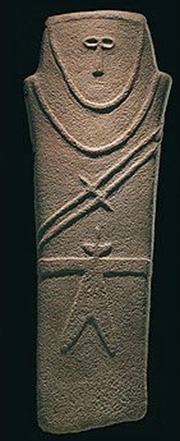

The sensitivity and the sense of mystery evoked by the anthropomorphic stone stelae from north Arabia of the 4th millennium is quite remarkable. These are outstanding works of art by any standard of judgment and the large figure from Al-Maa from Al-Maakir/Qaryat Al-Kaafa near Hail in its pose of pensive contemplation, is from the hand of a great master.

Over the following millennia, towns emerged in the oases of Arabia and Tayma in the north was one of the greatest. A large painted bowl found there of the 1st millennium BCE is one of the finest of treasures in the National Museum in Riyadh. In its setting in the Louvre with the elegance of its complex bands of decoration in brown slip-paint, it simply glowed.

In later times, Tayma was the scene for the celebrated episode between 553 and 539 BCE when Nabonidus (Nabu-na’id), the last king of Babylon, took up residence there and made it the capital of his empire. The king ensured that Babylon thereby controlled the northern distribution network of the valuable trade in frankincense and myrrh that by this time had long been carried by camel caravans from the incense producing lands in ancient South Arabia.

The Paris exhibition displayed the broken upper half of a stele and its base found at Tayma by a 2004 Saudi-German expedition. It is inscribed in cuneiform script and shows the king and symbols of the Babylonian astrological deities, with the name of Nabonidus written on the base, the first inscription in his name ever found at Tayma.

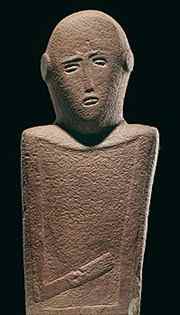

A funerary stele, inscribed in Aramaic marks the complex culture of Tayma after the ending of Babylonian hegemony. This stele is of a well-known South Arabian type of the 3rd-2nd BCE, its human face reduced to a stylized, powerful abstraction. Such stelae are rare in northwest Arabia and it may derive from the connection of Tayma with the South Arabia kingdoms via the rich and ancient trading city of Dedan, the modern city of Al-‘Ula’.

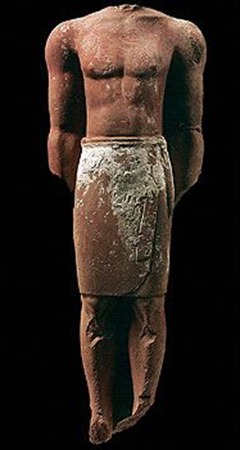

Of a quite different order are the immense royal statues of the Lihyan kings from the Khurayba area of Dedan which had so forceful and memorable an impact in the Louvre exhibition. They are a tribute to the skilled sculptors who emerged among the Lihyan Arabs. These sculptures portray the kings of the Lihyanites and they inevitably prompt a re-analysis of our perceptions of the Lihyan monarchy, its society and its art. Until very recent years, the Lihyanites were only known to scholarship as shadowy predecessors of the Nabatean kings of northwest Arabia, using a distinctive Lihyanite script. With these startling newly-found sculptures, displayed for the first time in Paris, the Lihyanites take on a new prominence in Saudi Arabia’s cultural history which has yet to be completely assessed.

The figures that were displayed are of red sandstone and were found in recent excavations by King Saud University at a shrine at Dedan and they bring the total of known Lihyanite royal sculptures to 14. Archaeologists Hussein Abu Al-Hasan and Sa‘id Sa‘id in the exhibition catalog record that the sculptures were originally set against a temple wall, each beneath a portico and set on a terrace. Where an earlier generation of scholars dated Lihyanite sculptures to the 1st C. BCE, they are now attributed by Saudi archaeologists to ca 4th to 3rd C. BCE.

They follow in the tradition of Egyptian sculptures of a type established by the 26th Dynasty of Egyptian Pharoahs (between 685-525 BCE). The muscular bodies and the full square frontality of the Egyptian figures are precisely echoed in the Lihyanite sculptures. In the same way as Pharaonic sculptures, the Lihyan figures were painted red and their kilts were white. The paint had been periodically refurbished as the Louvre conservators note in the catalog. However, the body of one figure was covered in black tar, suggesting an African connection.

None of the Lihyan sculptures exhibited reaches its full height as all of them long ago lost either their heads or their feet, but even in this condition they reach from 2.30 m to 2.56 m in height — originally they were an extraordinary 3 m+ in height. It seems that they were smashed intentionally, perhaps during the events that led to the rise to power of the Nabatean kings at the city of Hegra, 15 kms to the south of Dedan.

HEGRA (Madain Saleh)

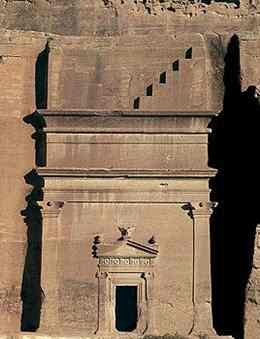

Hegra, the Al-Hijr and Madain Saleh of the Holy Qur’an, is the most prominent archaeological site in Saudi Arabia, its international importance reflected by its registration as the Kingdom’s first UNESCO World Heritage site in 2008. In the Louvre exhibition, the grandeur of Hegra’s Nabatean monuments was conveyed by a series of impressive photographs that come near to conjuring the feel of Hegra for those who have not visited it.

The Nabateans were a north Arabian tribe, well established at their capital city of Petra in Jordan as early as the 4th C. BCE. Before the 1st C. BCE, the kings of Nabatea established a trading outpost at Hegra in the territory of the Lihyanite kingdom and when the Lihyanites fell, the Nabateans emerged as their successors, making Hegra their southern capital.

The Nabateans were a north Arabian tribe, well established at their capital city of Petra in Jordan as early as the 4th C. BCE. Before the 1st C. BCE, the kings of Nabatea established a trading outpost at Hegra in the territory of the Lihyanite kingdom and when the Lihyanites fell, the Nabateans emerged as their successors, making Hegra their southern capital.

The wealth that the Nabateans gained from control of the international incense trade route between south Arabia and the Hellenistic and Roman world of the Mediterranean is reflected in the great carved tomb façades that the kings and high families of the Nabateans had carved from the red sandstone mountains of Hegra and Petra alike. The  inspiration of their designs is a combination of the architecture of the Hellenistic world and elements deriving from Assyria, Iran and southern Arabia.

inspiration of their designs is a combination of the architecture of the Hellenistic world and elements deriving from Assyria, Iran and southern Arabia.

The inscriptions at Hegra are largely written in Nabatean script while some are in an early Arabic. They record precise legal dedications, showing a society ruled by law. A system of fines existed for those breaking the law. Greek and Latin sources describe the Nabatean kingdom as peaceable and well governed, and extremely prosperous and sophisticated in its tastes.

The Nabatean inscriptions on the tombs at Hegra are precisely dated and incised directly into  the rock, thus ensuring their preservation.

the rock, thus ensuring their preservation.

There are far fewer inscriptions that help dating at Petra and this has led to a complicated problem for archaeologists estimating the date of each Petra tomb. By contrast, the chronology of the surviving Hegra tomb façades is much clearer.

A number of family stone carving businesses existed at Hegra with skills passed from father to son through generations. These craftsmen were highly respected as master-builders and their status is indicated by the references to their names in the inscriptions commissioned by each tombs’ owner.

The Nabateans’ wealth eventually provoked the greed of the Romans to such an extent that the emperor Trajan annexed the entire kingdom in 106 CE and the line of Nabatean kings was ended. Roman activity at Hegra is testified by a Latin inscription displayed in Paris and excavated at Hegra in 2003 by Dr. Daif Allah Al-Talhi. The inscription is dated to 175-177 CE and records the rebuilding at Hegra of a structure that had collapsed.

The inscription declares that the project was dedicated to the honor of the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus and that a Roman centurion of the Third Cyrenaica Legion, stationed at Hegra, ordered it. In true colonial style, he ensured that the people of Hegra paid for it themselves and left it to the first local citizen of the city, ‘Amru the son of Haian, to organize matters.

Recent research by Laila Nehmé and her colleagues has been very productive in interpreting Hegra. It has revealed a city wall enclosing much of Hegra. The Nabateans had a custom of holding lavish formal banquets, but the recent excavations show that the Hegra banqueting halls ceased to be used after the early 2nd C. CE. The exhibition catalog suggests that these banquets were banned as a means of suppressing anti-Roman dissidence among the Nabatean Arabs, shorn of their kingdom and their independence.

As the Roman Empire weakened in the 3rd C. CE, Hegra and the rest of north Arabia drifted out of Roman control. The Arab tribal confederation of Thamud who had lived in north Arabia for many centuries emerged as a significant group in this period at Hegra. The Holy Qur’an records how the Thamud leaders rejected the teaching that Allah sent through the Prophet Saleh (pbuh). It is from these events that Hegra acquired the epithet of Madain Saleh. For their arrogant rejection of the Prophet Saleh the Thamud were destroyed by earthquake as the Holy Qur’an describes.

Earthquake and volcanic eruption have been major factors in the history of the Middle East. In the case of the Thamud, the Holy Qur’an seems to narrow down the date of the earthquake that befell them to somewhere between the end of Roman rule at Hegra and the start of the teaching of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) in ca 610 CE.

Author: DR. Geoffrey King | Source: Arab News [November 10, 2010]