When it comes to scary monsters, the ancient Egyptian devourer is always going to be hard to top. With the head of a crocodile, the body of a lion and the hindquarters of a hippo, it is certainly more exotic than the average Halloween outfit.

And, though it sounds risible now, for centuries in Egypt the grim fear of meeting this evil, "cut 'n' shut" beast on the other side of death helped to shore up an entire system of belief, a system shared by pharaohs and artisans. In fact, the devourer played a key part in one of the most intriguing tenets of faith humankind has yet come up with: The Book of the Dead.

And, though it sounds risible now, for centuries in Egypt the grim fear of meeting this evil, "cut 'n' shut" beast on the other side of death helped to shore up an entire system of belief, a system shared by pharaohs and artisans. In fact, the devourer played a key part in one of the most intriguing tenets of faith humankind has yet come up with: The Book of the Dead.

Next month, the most comprehensive exhibition to be staged on this ancient doctrine of denying death will open inside the Reading Room at the British Museum.

It will showcase, for the first time, the entire length of the Greenfield Papyrus, which, at 37m, lays out each detailed stage of a journey the ancient Egyptians believed they would all have to make when mortal life had slipped away.

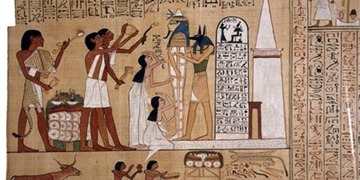

On display, too, will be a succession of paintings taken from the papyri of Hunefer and of Ani, probably the two most famous works to depict the many episodes, or trials, that together constitute The Book of the Dead.

Both papyrus series are owned by the museum, which has the widest collection of these rare, priceless manuscripts in the world.

From the looped outline of the ankh symbol, to the falcon beak of Horus and the jackal head of Anubis, the figures and signs depicted on an Egyptian papyrus are instantly recognisable, even when their meaning is unclear. According to John Taylor, the British Museum's expert in these ancient last rites, the best way to think of The Book of the Dead is as a reassuring map to the afterlife. "It is a kind of a combination of a spell, a talisman and a passport, with some travel insurance thrown in too," he explains.

So the papyri, which were made for well-to-do customers between 1280BC-1270BC, each function like an A-to-Z of the netherworld: full of symbols and landmarks that orient and guide the dead soul through a projected ghostly landscape - to a part of a city not yet visited.

The papyri are kept together at the museum in a seemingly rather low-tech way, amid the smell of dust and glue inside what looks like a geography teacher's cupboard from the 1970s. Taylor, who has curated the new exhibition, says he is still amazed by the intricacy of the work.

But many are extremely fragile and the temperature and humidity in the storage room is held at a constant level. The majority of the papyri in the museum's collection came to Britain in the 19th century and were part of the booty of returning diplomats and aristocrats. Those sheets that were put on public show in the sunlight bear the scars.

In an early attempt at conservation, many of the papyri were pieced together like jigsaws and then mounted on brown paper. Neither the meaning of the words nor the images was fully understood at the time, so pigments and brushstrokes were painstakingly matched by eye. And it is the papyri that will be at the core of the new show. Although a couple of stylish mummies and some golden coffins and mummy masks will go on display as well, alongside the sparkling bling of the amulets and charms, it is the papyri that give everything its context. Before they were comprehensively deciphered, over the decades after the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, it was supposed that they told individual life stories. Now, it is clear they were an essential piece of funerary kit and were produced by scribes who toiled in workshops attached to temples.

Sometimes, the scribes worked at speed, perhaps leaving the images sketched out in crude black ink, like a modern film storyboard. But if the client was rich and there was time, the papyri were ornate and colourful.

Taylor, who taught himself the rudiments of hieroglyphics at school, is by now so steeped in the ancient art he can spot the styles of specific scribes. "But I'll never know their names, of course," he says wistfully.

Ani's elaborate papyrus, thought to be among the best surviving examples in the world, was 19m long. But even here a mistake is visible at the join between two sheets of papyri because the job was being done by many hands across a workshop floor.

The script of a papyrus is read from one side to the other, depending on which way round the depicted animal heads are facing. The spells and incantations appear alongside the images they evoke and they commonly deal with the sort of problems faced in life, such as the warding off of an illness. They are usually rather straightforward: prose rather than poetry. "Get back, you snake!" reads one for protection against poisonous serpents.

For the ancient Egyptians, the act of simply writing something down formally, or painting it, was a way of making it true. As a result, there are no images or passages in The Book of the Dead that describe anything unpleasant happening. Setting it down would have made it part of the plan.

There was, however, always a heavy emphasis on dropping the names of relevant gods at key points along the journey.

The museum exhibition will twist and wind, like the route taken by dead souls, and visitors will have to negotiate gateways at each stage.

In one section, the ceilings will narrow to the height of the tomb, but it will not be necessary, as it was for a dead Egyptian, to offer the name of a god as a kind of magic password.

The best-known stage in this journey through the afterlife is the weighing of the heart. Scales watched over by Anubis are used to balance the heart of the dead soul against a feather, which represents truth. If the heart passes the test, then the way forward is clear. If not, the unseen threat is that the devourer who hovers below will snap up the organ in its crocodile jaws.

Other stages of the journey are just as fascinating, if less perilous. A board game called senet, which looks a little like a cross between chess and backgammon, must be played with a god. Depicted elsewhere is the sinister ritual of the opening of the mouth, which involves a series of macabre tools that were often buried inside a tomb with the dead body. At a pivotal moment, the dead soul also has to satisfy the demands of 42 separate judges, saying each one of their names out loud to please them.

And this is where the papyrus crib sheet came in. It carefully listed each god in the correct order for the recently deceased client.

If all else failed, at the final hurdle there was a handy spell designed to conceal all sins and mistakes from the gods by making them invisible.

And then, when a dead soul finally completed the journey, there waiting for them at the end, so the papyri all promised, would be an ancient Egyptian version of heaven: full of reeds and water and looking very much like the Nile Valley in the year of a good harvest, replete with grain, food and drink.

The crowning moment arrived at the sudden appearance of the sign of the life-giving lotus flower. The point of the whole experience for the moribund traveller was a vital reunion with their dead ancestors. "The family unit was crucial," explains Taylor. "You cared for your dead family because they were still there, on the other side. They could communicate with you and had power over you. So people wrote letters to the dead asking things like, 'Why are you still punishing me?"'

Death, he adds, was a familiar part of daily life and ancient Egyptians felt closely connected to it, if not quite comfortable with it. Most people died before they were 40 and so mapping out a plan for the afterlife was a way to handle this probability.

Intriguingly, evidence reveals that there were some sceptics who were prepared to question the likelihood of a paradisal "field of reeds" waiting for everyone on the other side of death. Taylor confirms that documents have been found in which these sceptics seem to query the point of The Book of the Dead. Most, however, seem to have decided that buying a papyrus was an insurance policy in case it turned out to be true.

Among all the varied ideas contained in The Book of the Dead manuscripts there is no sense anywhere that the scribes were setting down history for posterity. Neither is there, Taylor says, any striving for objectivity in the way sentiments are expressed. Instead, the papyri are a practical piece of political and spiritual spinning, a means to an end delivered at an agreed price.

And yet because these papyri deal with fear and death and hope, they cannot help but provide an immensely absorbing window into the minds and emotions of an ancient society. Their images and hieroglyphs have now become the emblem of all that is mysterious to us about this remote culture.

Author: Vanessa Thorpe | Source: NZ Herald [October 30, 2010]